“Surveillance capitalism is the self-authorized extraction of human experience for others' profit.”

Everlane CEO Michael Preysman was recently quoted as saying ‘basically’ no online-only companies are profitable, and this is spurring their investment in brick-and-mortar. He’s not wrong - there are real, hidden, costs with doing business online and many of those are outside of your control and susceptible to changes in market demands. Everything from shipping rates to paid social rise and fall with market demands.

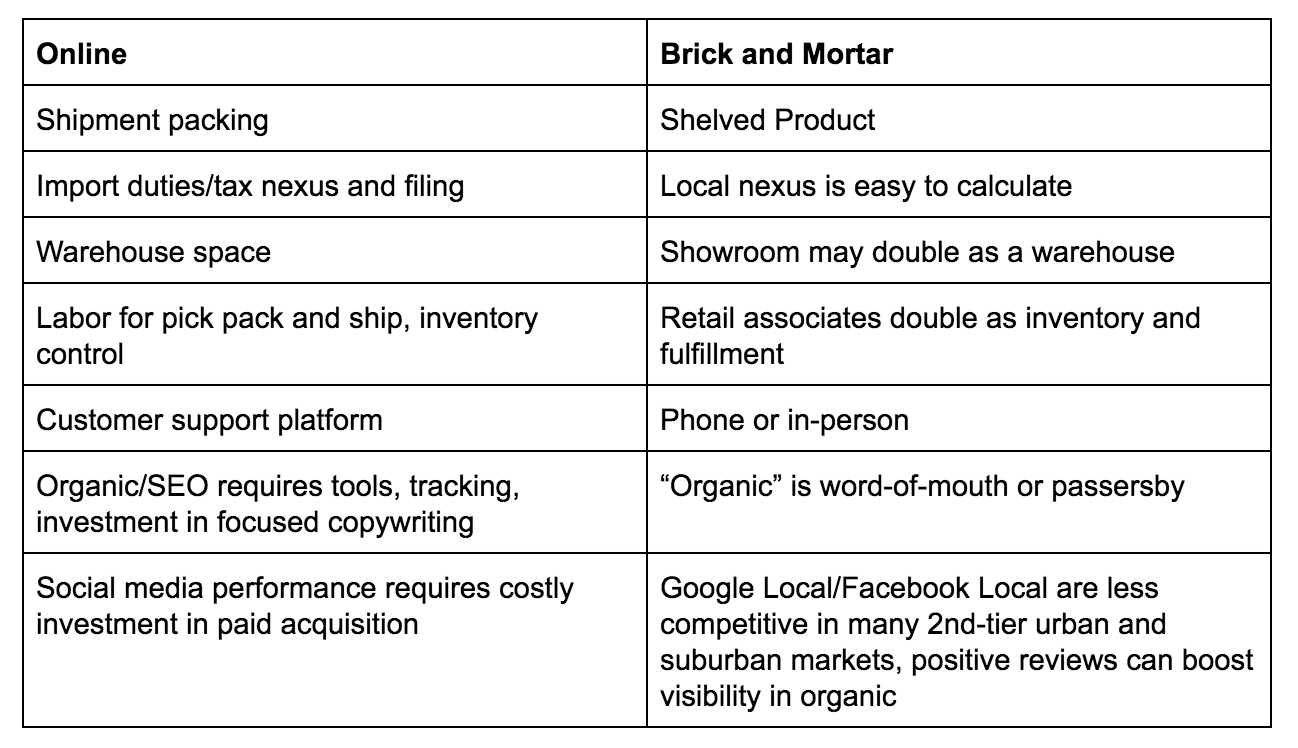

In a recent Twitter thread I unpacked these hidden costs. This is by no means a comprehensive list but it underscores my point:

In short: doing business online requires additional investment beyond what similar needs are of a local shop. In trade for that investment, you gain global reach beyond the confines of your local area. But let’s not kid ourselves, it’s not “simple” running an online business, and even if you have the potential of global reach - how many brands do you know live up to their full potential? Name a few. I’ll wait.

So it makes financial sense to hedge - to spread some investment around - between your online and offline presence in the lifecycle of your brand. While CAC rises and it becomes more expensive to acquire customers online, rents in the real world are quite stable and can often be had at a bargain. Where tech salaries are on a 9 year growth trend and entry-level Amazon hires make 6-figure incomes local wages in-store are relatively flat and predictable. Wood and plaster, it seems, can be had cheaper than ones-and-zeroes.

Here’s something that very few local businesses can claim parity on with regard to online shops: access to customer data. It’s all-too-easy to point a site at Google Analytics and slap on a Facebook Pixel these days. With those two pieces alone you have the ability to quantify interactions, create audience segments, analyze behavior, adapt to customer interaction, and create cohesive brand engagement across a variety of platforms on every device imaginable.

Unless Clover or Square have made significant leaps forward in technology that I haven’t heard of yet, operating a local brick and mortar can seem to put you at a disadvantage.

But for all of these advantages, I’m becoming more and more skeptical of whether we should be utilizing these tools at all. They are, after all, designed to shape customer behavior. While they’re often framed as tools to ‘reduce friction’ they’re really tools of manipulation - where we can apply the scientific method to shorten the path between impulse and action. The friction is all-but-gone in the post-Amazon world.

💡Suggested read: Friction = Good by Brian Lange on INSIDERS #006.

I recently dug into a very challenging read: The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshanna Zuboff. It’s an eye-opening book, and I highly recommend it. Surveillance capitalism is an offshoot of market capitalism.

Surveillance capitalism sees every interaction and experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data. Although some of these data are applied to product or service improvement, the rest are declared as a proprietary behavioral surplus fed into prediction products that anticipate what you will do now, soon, and later.

As capitalism evolves to adapt to every modern challenge, in this brave new world our every interaction builds a statistical model of us that predicts (with stunning accuracy) our ability to be manipulated. Eventually, it’s no longer enough to know our behavior, it now becomes paramount to shape our behavior. And now knowledge transforms into power.

The machine knows us. The machine quantifies us. The machine manipulates us. And now the machine is automating us. How many times do you have a Prime delivery and you can’t even remember having ordered the item in the box? Amazon just last week announced Echo Frames, an always-on voice-first device which responds to the wearer’s incantation of “Alexa?”. The surveilling has now become mobile, beyond the limits of our home or our device. It’s now fixed outward in the direction of our gaze.

One could argue that, like Neo in the Matrix, we’ve been reduced to batteries powering an economy that depends on our consumption to exist, lest it all fall apart.

As the customer becomes more demanding of information about the source and quality of materials, their countries of origin, the chemicals that went into the manufacture of the goods, and the nature of the workforce that went into the production of the products they consume the retailer has to adapt. The consumer has the ability to vote with their wallet, and many brands are responding with radical transparency.

And if the attention economy is The Matrix, then our local places of business have become Zion. They are a logical place of refuge for those seeking shelter from being quantified by an algorithm. You can choose to be known; you can choose to ask for help. You have agency when you step into the local bookstore. If you do submit to being known you may also submit gradually to recommendations. Eventually, you find yourself persuaded by the recommendations of others in your local community, but these are built on shared experience and not the result of your having fallen into a lookalike audience.

This generation is becoming increasingly aware of digital wellbeing - they’re not just limiting their kids screen time, they’re curbing their own social media usage, too. The market rises to respond, and new marketplaces emerge for brands that espouse similar ideals. Certified B is providing hope that companies with quality products and a moral imperative to do no harm can exist and make a profit. There has been a resurgence in local green markets and coops. Even bookstores are making a comeback. Offline shopping provides community and continuity, while also acting as a haven for those seeking to escape being quanted to oblivion.

Perhaps we can course-correct as a new generation becomes more conscious of the effects of filter-bubbles, and as we legislate for privacy and consumer protection. In her book, Zuboff makes the argument that ‘privacy’ and ‘monopoly’ are not words that accurately describe what Facebook and Google have become. We don’t have words yet to describe their ubiquity in our lives and the power they wield.

Look. These are tough issues, and Brian and I spend the majority of our full-time jobs thinking about how to grow revenues for businesses that have come to us for help.

.png)